Sign in

Don't have an account with us? Sign up using the form below and get some free bonuses!

In positive parenting, the power of a hug is some of the best preventative medicine that exists for the adult-child relationship, even with children who aren’t our own.

A girl I'll call Juniper, who was then two and a half years old, was standing with my child and me in the doorway just before we joined Teacher Tom for outdoor story time. It was the very first time I'd ever met her. I was the last adult chaperoning kids out of the building, so I couldn't join story time with my child until I was sure all the kids were accounted for. Juniper had no intention of joining us, though, as I could clearly see from her body language. As Teacher Tom noticed my child and me waiting in the vestibule, he beckoned for us to join him. A lot of people were waiting for us. He was unaware that I was encouraging Juniper, who was cowering in a corner, to follow us.

In an attempt to connect with Juniper, I crouched down to her level and reached out my hand. I'd have held her hand, hugged her, or picked her up, if she'd indicated any of those options were acceptable. To my surprise, however, she jumped at me like a mini-superhero, then started throwing punches and kicking me. She tried to bite my arm. Holy moly.

Despite being momentarily stunned, I heard myself think, "I'm going to Janet Lansbury this." (I didn't know Janet was a verb. I always thought she was an early childhood expert.) As calmly as I could muster despite Juniper's flailing limbs, I held her shoulders at a safe distance from my body. I looked her in the eye and said, "I won't let you hurt me. I'll help you through this." Immediately, she calmed, took a final halfhearted swing at me, and took off running down the hallway of the building. Knowing I couldn't leave a child alone in there, I invited my child to follow me as I gently pursued Juniper. I gave her plenty of space.

To be clear, I use positive discipline as a synonym for teaching. I don't support force or punishment of any kind as a parenting approach. In my experience, a hug and almost any form of positive parenting go so much farther than anything punitive.

Before I continue with what happened, it’s helpful to understand some of the different approaches I could’ve taken, based on different parenting styles. This child didn’t need to be mine for the same neuroscience to apply.

If I acted like an authoritarian parent, it likely would've presented as me yelling after her, catching her, and picking her up against her will. Flailing or not, I'd plop her down into to story time. Traditional authoritarian parenting (the most commonly punitive option) centers around adults controlling children. It has negative long-term consequences for the parent and child relationship, as well as for the child

herself, as John Gottman, Ph.D. describes in Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child (afflinks). Forced compliance does nothing to support children’s emotional intelligence or attachment to their caregivers, and I certainly wasn't going to make this little stranger "behave" somehow.

On the opposite end of the parenting style continuum from authoritarian parenting is permissive parenting. However, Dr. Gottman, Janet Lansbury, and many other experts caution that permissive parenting isn't the antidote to authoritarian parenting. It, too, carries risks for the child. Children need loving and reasonable limits to feel secure. Permissive parenting might’ve looked like my letting Juniper run wherever she wanted, and not saying a word to her about it.

Neither approach would've given Juniper helpful tools upon which to rely in the future. Moreover, if she happened to be a highly sensitive child (HSC), odds are good that anything punitive might have sent her into an even tougher emotional situation.

This balanced type of positive parenting is called authoritative parenting. Note that although the name authoritarian parenting, which is negative, sounds like authoritative parenting, the latter is positive.

In any case, this certainly wasn't the time for a sticker chart or a "red behavior card,” which is common in many preschools. (I'd argue that no time is right for those, but that's another post.) As Ross Greene, Ph.D., argues in The Explosive Child, "...The reason reward and punishment strategies haven't helped is because they won't teach your child skills he's lacking or solve the problems that are contributing to

challenging episodes..." These methods don't teach children how to cope when they're emotionally overloaded.

Conversely, positive parenting is linked with better long-term outcomes for the child. This is true not only short-term, but also for the child's long-term wellbeing (1). Examples of positive parenting styles include RIE® (2), attachment parenting, authoritative parenting, and many others. Descriptions are readily available on the Internet, and my website has a list of my favorite positive parenting books. (Yep, I've read everything there. I share only the ones that have solid, actionable messages and that promote positive parenting.) I wish I had a dollar for every style of parenting in the dictionary these days, but truthfully, the names don't matter much.

All that said, I wasn't entirely enthusiastic about pursuing this small Mike Tyson. However, I realized that this responsibility was on me even if I didn't sign up for it.

I trusted that I was there for a reason. I needed to find that middle ground that would help Juniper trust that I was on her side while still accomplishing what we needed to do: reconnect with the class.

So, I offered her a hug. Totally bewildered for a moment, she yelled, "No!" And then she sucked her thumb, rocked herself, fell to the floor crying, and then got up and ran at me again. For a moment, I almost blocked my body for safety. I saw something different in her eyes, though, so I stayed within reach. She ran to me as if I were a long lost friend and collapsed into my arms, bawling her little eyes out.

She hugged and hugged and hugged, leaving my daughter and me surprised, but on we went hugging. Her tension melted away entirely. We proceeded to story time peacefully.

At that point and for reasons unbeknownst to me at the time, I told her that I have a "hug button" on my shoulder. Anytime she'd need one, she could come and touch my shoulder, and I'd know what to do. I made sure to always crouch down when she came near, just in case she needed to push it.

If any child were to put something unsafe in her mouth and start running down the hill on the playground, it was her. With some false starts, I learned that following her and asking her to remove the choking hazard would backfire. It was all the convincing she needed to keep the aforementioned item there. When I pushed too hard or sounded forceful, fearing for her safety, she’d take off running and create an even greater safety risk to herself.

Once I realized that, I chose to address her potential issues proactively. The moment I saw her put something in her mouth, I'd crouch down and call her name from wherever I was on the playground. I'd stay put. She'd look over, and I'd point to the invisible hug button on my shoulder.

More often than not, she'd nod and come running my direction (sometimes with the aforementioned object still in her mouth, but it was progress). She'd hug me for as long as she needed and then relinquish the item.

Except for when she didn't come. I'm not perfect (more like a million miles from it), and sometimes my tone would be too worrisome for her. Or sometimes I'd think I'd done it "right," but she was too emotionally overloaded to connect.

I lost count of how many times a proactive hug completely deescalated potential problems. I'd see a "look" on her face that signaled trouble, so I'd offer a hug. And just like magic, all was right with her world again. Some of the other kids in class even joined in on the “hug button” initiative.

On the last day of class, Juniper walked up to me and offered me a hug for the first time, proactively. She'd never done that before. I happily accepted. Much to my surprise, she cupped my face in her little hands and she whispered, "I love you." It was the perfect 2.5-year-old translation of "Thank you for understanding exactly what I needed when I didn't have the words to explain it."

And I love her, too, in the most wonderful way of loving a small person I'll likely never see again. She helped show me the power of positive parenting from a lens outside that of my own family. She reinforced that it's better not to chase my child; but instead, to be rock solid and a "safe place" emotionally. She confirmed what the the gentle parenting books say should happen when a child feels connected. My own parenting is better for the important positive parenting lesson she taught me.

There's a lot to be said for the power of a hug.

_____________________________________________________________

Source (1): https://www.parentingscience.com/authoritative-parenting-style.html

Source (2): https://www.rie.org/educaring/ries-basic-principles/

I recall one afternoon shortly after my own daughter turned two. She looked at me and announced ever so confidently, "Park. No pants." Hold the phone---when did she learn to say "park?" And was she actually

requesting to go there without any pants on? (She was. We went; her, without pants, and me, fully clothed. It was warm. No one batted an eye.) I realized at that moment that the baby I'd just figured out, suddenly wasn't that person anymore. She was evolving before my eyes.

So, true. We do need to adjust our parenting at this milestone age.

Whereas before we had a child who was likely happy to be carried much of the time, we now have someone who wants to walk. (And by walk, I mean sprint precariously forward, and usually with turbo speed when stairs or vehicles are present.) Suddenly, we need to sprint after a fully functioning human body, and that's new to us.

Whereas before we could talk to our little person and he'd smile or babble in response, we now have someone who's forging his own opinions about things. Suddenly, we need to navigate a new opinion in the house, and that's new to us.

The human brain will never again grow as fast as it's growing right now in these first few years of childhood. As much as it is for us---the adults---to process, it's even more overwhelming for the little people to whom this "growing up" thing is happening. Sometimes, it manifests in what adults perceive as suboptimal behavior, such as tantrums.

as tantrums.

One important thing to note is that throwing a tantrum isn't about disobedience; it's a little one's way of saying, "This is pretty overwhelming right now! Can you please support me?" Unfortunately, two year olds often lack the verbal skills, not to mention the development in the prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain that controls impulses) to help them do anything other than exactly what they're doing. Some quick brain science: the prefrontal cortex doesn't fully develop until around age 25.

I realize that when a child throws a temper tantrum at the grocery store or on the playground, it's inconvenient. Sometimes, it's downright embarrassing. If situations like that irk you, please know you're not alone. Remain calm; practice deep breathing.

If I had a single piece of advice around your child's big feelings, I'd suggest that you let go completely about what other people think and simply connect to your child. This connection is going to get you through age two, and all of the other years that follow. Now is a great time to practice.

And here's the crazy thing---most "terrible twos" spend very little time upset. In my personal and professional experience, two year olds are incredibly delightful most of the time. The amount of time they spend being curious, giggly, and affectionate far outweighs anything else.

Surprise people with your ability to see the joy at your child's newfound mobility and freedom, because it's new to him. We can learn to run faster.

Surprise people with your gentle support of your child's awesome new ways to show you "This is who I am and what I like," because advocating for herself is new to her. (And how freeing it must be to clearly know your boundaries like little kids do. What a gift they have this way!) We can learn to help our child navigate communication.

Surprise people with your flexibility around forced sleep times; we all sleep when we're tired enough, and this incredible desire to play with you every waking hour is new to your child, too. We can learn to adapt.

Part of respectful parenting means we learn to work with the child in front of us, even when it requires that we, ourselves, grow in our abilities. Additionally, it means we're intentional about the ways we describe our children to others. Our words matter and our kids are listening. Do we like them? Do we want to foster a positive connection based on mutual trust? As parents, we're called not only to be kind to them, but also to reflect that kindness in the words we use about them.

When someone mentions the "terrible twos" to me, I often reply with a shrug and respond, "Huh. I've always called them the 'terrific twos.'" 'Nuff said. One person at a time, we can change perception---because after all, our perception is our reality, isn't it?

Your two-year-old child is wonderfully fine, and more often than not, perfectly terrific.

I've had it with gentle parenting.

To clarify, I'm still giving children love, respect, and a whole lot of grace as they learn to navigate this thing called life. More than ever, I see the value of positive parenting not only in my own child, but also in those with whom I interact regularly. I'm fully committed to the notion of treating others, including children, the way I'd like to be treated. The "golden rule" is very much my parenting mantra.

You see, "gentle parenting" has turned into a marketing buzz phrase that, in many cases, is neither descriptive nor accurate. After having wasted hours on Pinterest last week looking for gentle parenting articles to share with my readers, I realized just how liberally people are using the term. The same is true for its nomenclature siblings: positive parenting, positive discipline, and conscious parenting, among others.

Once we dilute the "gentle parenting" term so much that it refers to almost anything we want to "accomplish" as a parent, it becomes meaningless.

Spend three minutes on most social media and you'll find things like:

In short, I don't trust an article, book, or well-meaning friend who says something is "gentle" if it isn't in sync with what positive parenting really is.

I don't know a decent parent anywhere who doesn't want to be gentle with his or her children. We all have good intentions.

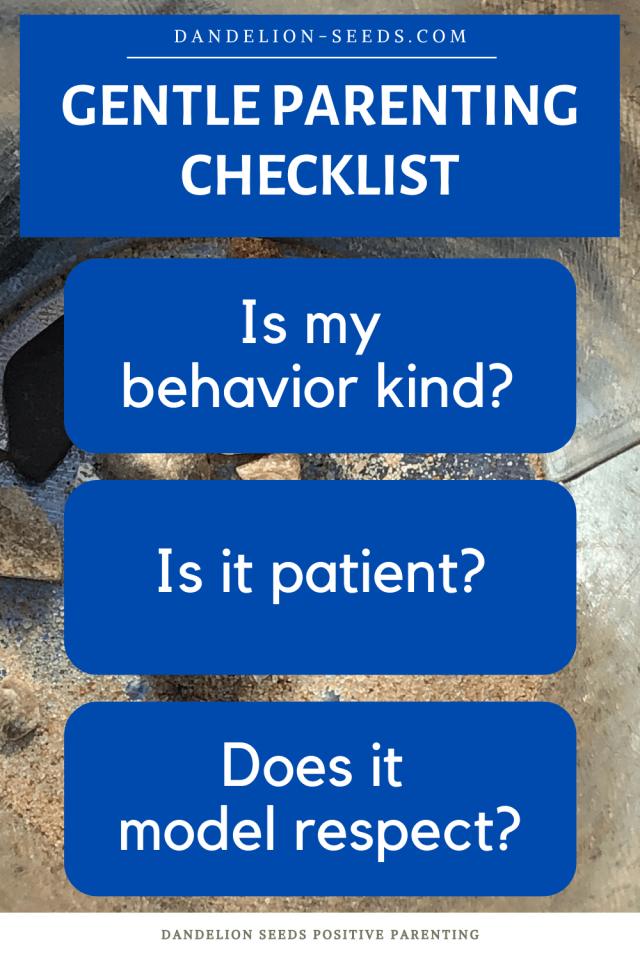

Skydiving, gambling, and motorcycle riding aside (and with respect to those who do those things without baby present), there are a few telltale signs that you've found the "real deal" when doing your positive parenting research. I've boiled them down to the basics that I keep in mind as a parent and educator.

I once joked on my Facebook page that I'd written the shortest parenting book ever. It included only a single question parents can ask themselves when deciding how to handle something with a child: "Am I being kind?"

In all seriousness, this really sums it up. What's the kindest response you can have to any given situation?

Is the sleep solution you're considering peaceful, or does it leave one or the other of you feeling unsettled?

Is the discipline situation your friends have suggested kind, or does it involve something designed to induce feelings of shame or regret?

Is the parenting book you're reading suggesting ideas that will bring you and your child closer together, or do the ideas inflict emotional strife on either of you?

Oftentimes, I make parenting decisions only after I've consciously assessed whether I'm choosing the kindest option I can in the moment. I never want to justify suboptimal parenting by thinking "It's for the best" or "I wish I didn't have to do this, but it's the only option." I assure you there's always a way to be kind.

I'll confess that even as a gentle parenting writer, I sometimes struggle with this one. We all have tired days, too-many-rainy-days-in-a-row-days, and we're-humans-who-sometimes-want-different-things-while-living-in-the-same-space days. Case in point: I intended to spend an entire screen-free day with my child the other day, but my computer broke when I was doing "just one thing" on it, and I ended up sufficiently grouchy that I had to fix it.

It wasn't my child's fault that my computer broke. She got antsy that I had to devote time to fixing it instead of playing, and I got frustrated by her antsy-ness. Her need was legit; mine was, too, in its own way. But as truly gentle parents, we know that our children's behavior is often a reflection of our own.

When we find ourselves feeling impatient, we don't punish our children for it or make them our emotional outlets. We find ways to stay connected amidst suboptimal circumstances. We actively seek out the emotional tools we need to help us keep our cool, understanding that our kids need us to model patience. That's how they learn emotional regulation, themselves---by observing us.

When we make a mistake, we apologize for it.

We don't equate immediate compliance with respect.

We understand that parenting is not about "How do I get my child to do (whatever it is)..."---that doesn't fit into the golden rule. We don't "get" people we respect to do things. We collaborate with them. Problem-solving works best in partnership with others.

We model what it means to engage in healthy, respectful adult relationships---because that's what we want for our kids when they get older. Their training starts now in their daily interactions with us.

We don't choose gentle parenting because it's the most convenient option. It's often downright hard, especially if it involves facing triggers from our own upbringing. (Wait, that happens? Heck yeah it does, and it's tricky emotional stuff to work through!) We have to examine our hard wiring. Often, we need to very intentionally rewire our brains to not do whatever the default response might've been in our family of origin. Oof. It's doable, though, if we're mindful about actively working on ourselves.

Of course I do. We just need to know what it really is (and isn't), and make the practice real in our own homes. It's absolutely worth discerning the good advice from the bad and understanding that just because an article or a book is labeled as gentle, it really needs to be gentle for it to foster the results we're seeking as parents. And as parents, what better result than a long-term, positive, and loving connection with our children?

Sarah R. Moore is an internationally published writer and the founder of Dandelion Seeds Positive Parenting. You can follow her on Facebook, Pinterest, and Instagram. She’s currently worldschooling her family. Her glass is half full.

Perseverance and hope for the future: Every once in awhile, adults receive the gift of a new perspective.

Late last night, a teacher friend of mine texted me and said she had the flu. She asked if I could substitute teach her play-based science class of four- and five-year-old kids the very next day. Already in my pajamas, I responded to her text, "Sure, happy to." She had no lesson plan for me; I had nothing particular in mind to do. I crowd sourced a bit among my Facebook friends to ask for ideas, but given how late it was and the other things I already had to accomplish that night, I had little time to prepare anything. And I definitely wasn't heading out to the store in my jammies.

Fortunately, having tried my hand at improvisational comedy awhile back, I didn't sweat it too much. Plus, I had a secret weapon: a wonderful book about engineering that I could weave into our science discussion. In truth, the book isn't about engineering so much as it's about perseverance.

If a kid falls off his scooter, he's likely to deal with the crash, move past it, and try again. If I fell off a scooter, I'd be more likely to say, "Well, that didn't work out so well! I'm going to do something else." Not that I'm a stranger to perseverance; not at all. But as an adult, I don't usually continue to test the strength of my bones if I fall down.

I digress.

The book I brought to class that addresses perseverance so beautifully is Rosie Revere, Engineer (afflink). Without spoiling the story, I'll divulge that Rosie wants to invent something to help her great aunt. However, her plans aren't working. In one attempt after another, she hits roadblocks. She's tempted to quit.

I didn't plan ahead of time to do this, but every time I got to a natural stopping point during the story---every time something didn't work out---I'd ask the kids, "Should she stop trying?"

Every time I asked, they'd passionately yell, "Nooooo! She should try again!"

One boy responded so emphatically that he fell down.

And again, Rosie would try and then fail. So, I'd ask, "Should she give up and do something else?"

"No! She needs to keep trying!"

And we kept on like this throughout the story. I could tell one or two kids were starting to worry that it might not work out, but nonetheless, they all held on tightly to hope for Rosie's future. And they never strayed from it. They simply believed.

These kids kept believing everything would be alright as if no other option existed. Things simply had to work out. Their faith was unwavering; they trusted. They held steadfastly to their confidence without flinching.

Somewhere around three quarters of the way through the book, I realized that these children were giving the adult in all of us an incredible gift. There was beauty in their unquestioning belief that everything would be alright; faith in the positive and unwavering results of perseverance; simple trust that stories can have happy endings. Without knowing beforehand, I realized this was exactly what many adults need for their own own hope for the future. It's not that they didn't see the setbacks. They obviously did. However, they didn't believe that setbacks alone should make someone stop trying.

Their innate belief in goodness and hope for the future was just...simple. No one "taught" these kids to believe; they just do. And I caught myself wondering why adults often doubt so much. Why I often doubt so much. Even fairy tales don't always have happy endings. Kids know this, yet they maintain their hope. Why shouldn't we have just as much faith?

And the thing is, we can have that faith that things are going to be alright. We can kick our cynicism out the door and feel so much lighter. It doesn't mean we're not real, nor does it mean we're blind do the realities of life. All I think it means, really, is that we can release our long-held beliefs that things might not be okay, and replace them with trust and hope. Even when setbacks slow us down, they don't need to stop us from pursuing what's important. Things might just turn out okay, after all.

We can make optimism our default. I saw proof of that in the children.

I was always a highly introverted child. It showed. For instance, when I was in high school, I learned that for my dance group's upcoming graduation dinner, the other dancers selected me to receive the spoof award for being the "Most Reserved." Knowing how much I despised being called by a "label" like this one, my Mom suggested that I tape a sign that read "I AM NOT SHY" to the back of my underwear. She said that when I walked up to receive the award, I should moon everyone with my, ahem, (not shy side). Although I appreciated her sentiment, I did not take that advice.

Fortunately, the award never happened, but the message to me was clear. I'd known since I was little that I was simply wired differently from some of the louder kids. And being the good parent that she was, my Mom supported me in that.

In general, the mainstream society in which I live views a gregarious extrovert as socially "good," whereas quiet seems to imply some kind of problem. It isn't a problem at all, of course. Well-meaning adults often pursue introverted children who aren't quick to respond with a sweetly teasing inquiry of "Oh, are you shy?" No matter how good-natured the intention, a child can perceive this as, "You, little human, are not okay as you are." Let's fix that.

In truth, the child may not be shy at all. He may just be an observer who wants to find acceptance in the world. We all want that acceptance. Splitting hairs? Nah. For some, it’s actually quite different, and both can be completely developmentally normal. There's a difference between lacking confidence and being an observer who's sure of oneself. Some kids just prefer to enter the pool through the shallow end, so to speak.

Going slowly gives introverted kids the information they need to feel comfortable in new situations. Regardless of your child’s confidence, it's important for an extrovert who might not share the same "wiring" to understand that the seemingly innocent question about shyness can embarrass or cause pain for some introverted children. Talking with someone who's not a parent, sibling, or close friend might be a completely different experience for that child than it is for someone else.

No, it's not. Shy is a feeling alongside a behavior, as in "I felt shy and hid behind my mom when everyone in the room looked at me." Introverted simply means that someone feels recharged after being able to spend time alone, sometimes with a small group of close friends. Spending time with large groups of people can feel emotionally draining. It's usually temporary and is not a reflection of the child overall. Conversely, extroversion means that someone gets his or her "energy" from being around other people.

It's more about the types of interactions that deplete or invigorate us than it is about how we act in any single situation.

No, it's not. Introverted children are not always highly sensitive, nor is extroversion a trait of lack of sensitivity. Plenty of highly sensitive children like to spend time with others and get a lot of energy from being around others. The behavior of highly sensitive children varies considerably from child to child. That said, according to Dr. Elaine Aron, 70% of highly sensitive children (HSCs) are also introverts, so there's a lot of crossover.

Here are some ways you can support them "in the moment."

To you, it might just be another kid's birthday party. To your child, it might be "a place where people I don't know look at me and adults try to talk to me, and noisy kids are everywhere." Rather than telling your child what others expect of him (which she can perceive as pressure), state just the facts and describe what your child is likely to see there. Then, remind your child that you (or another trusted adult) will be with him the whole time. Finally, agree on a script of what he can say if he needs support. If talking to another adult without your involvement is tricky for your child, consider giving him a small "help card" to show that adult, instead.

If you're staying present with your child, try this.

If someone does say something to your child, then ask your child something like this (within earshot of that person): "Would you like to respond, or shall I tell them you prefer to observe?" There are lots of variations you can try here. Now that I have an introverted child of my own, I've had lots of opportunities to practice with her. Once we graduated from this question, we moved onto, "Would you prefer to say 'hi' or wave?"

Remember the importance of your loving, supportive touch along the way. Introverted children need their parents to follow their lead and reassure them in verbal and non-verbal ways. Your positive support will make the experience less hard, and much more positive, for them.

It's fine to encourage without pressuring. One helpful hint is to wait just past where you're comfortable and give your child enough time to respond. Sometimes it just takes a moment; release your expectations that they won't do it. Maybe they will!

Here's how:

If she chooses not to engage with someone who's talking to her, simply tell the other person: "She prefers to observe until she knows people better."

It's sometimes tempting to overcompensate for child who isn't responding to another adult (or child). If you apologize for your child's lack of response, it might placate the other person, but it sends the message to your child that he's done something wrong. Of course that's not your intention!

What should you do instead if your child isn't responding? Simply smile at the other party and continue the conversation normally. It sends that person AND your child the message that this is no big deal. That's great for your child's comfort level and self-esteem. We all feel more compelled to engage when we lack pressure to do so.

"Shy" and all its word-cousins have a stigma in the culture where I live, although they shouldn't. In many countries, it's actually perceived as rude if an extroverted someone is too over-the-top with energy (and words). In my home, we've banished all references to shy, reserved, and similar; instead, if we use any label at all (and we try to avoid them), we use it only as a verb. With child-first language, we say, "My child prefers to observe." I want to raise her knowing that labels don't define her. She's not my "shy child." She's my child.

It's helpful to listen to your children and seek understanding of what resonates with them. Every child's personality and preferences are different.

Spend time talking about a time you preferred to observe as a child. Introverted children love hearing that others have felt the same way they do. Even if you were usually the life of the party, you likely remember a time that you didn't want to be in the middle of the action. Present it as a positive; it's affirmation that your child is perfectly okay just as he or she is. Your child will flourish best when he or she feels like you "get" it. If you worked through a tricky situation, tell your kid how you did it. Explain your own strategies that have worked (while framing introversion in a positive light).

You know your child best. What kind of stimulation does he or she enjoy? Watch them for cues without projecting your own experience, or that which you've seen the media say is "normal." Are your kids happy spending time in simple play with family, or do they require many activities throughout the day with a large amount of socializing? If you contact your child's teacher with questions about how they learn best in class---in groups or individually---that can be a clue, too. If need be, rule out anxiety disorders that may be affecting your child's social-emotional comfort.

Quiet or not, you're raising a person who will look to you for validation that he or she is "good enough" for the world. There's a lot of pressure out there. And you, dear parents, when you support your children just as they are, are doing them a wonderful and necessary service.

If you don't have an introverted child, the best thing you can do is let the quiet ones be, without judgment or comment. The world needs all of us.

_____________________________________________________________

(Amazon afflinks): These books by Susan Cain and others helped me understand many introverted kids better than any others I've found; I highly recommend them. If you are, or know, an introverted or sensitive adult, they provide fantastic insight.

In the dance class I’ve written about before and that I help teach, the kids sometimes use colorful scarves as props during freestyle dancing. It’s really fun to watch them swirl and twirl, unless you’re watching littlest Julianne*, where you wonder how long it’ll take her to accidentally wrap up her feet and wipe out. The less fun part, however, is handing out the orange, yellow, green, red, blue, and purple scarves before the dancing begins. Almost all the kids are fine with any color, but a few want only purple. There aren’t enough purple scarves to go around, nor can two kids share the same scarf at the same time. When kids want the same thing, dance class quickly morphs into a crash course in economics, whereby some struggle with supply and demand. Scarcity makes the heart grow fonder.

When I hand out the scarves, it works best when I’m playful about it. I reach into the bag as if it were a magic hat full of rabbits. I act shocked and amazed each time a new color comes out, much to the delight of the kids. They get caught up enough in the game that they’re usually unconcerned with what color they get. If someone does get upset, some sincere active listening and empathy usually help them process and move on quickly. “Yes, I see how much you wanted the purple. You feel disappointed.” The child invariably affirms that I’ve understood correctly and then moves on with her dancing. If she’s still upset, although it rarely happens, she can process as long as she needs to.

I just don’t buy it. Maybe it’ll be an issue for some. But most of the time, it’s really not a big deal to them, at least not for age four (or so) and above. Many kids already have the emotional intelligence to delay gratification. They already know from their life experience that they’re likely to get a turn with the purple scarf, or whatever the object of their affection may be, at some point.

And most of them know exactly what to do about it if they want the same thing that another child has. The adults around them model sharing and taking turns every day, and like everything else, kids pick up on what they observe. Learning to share happens naturally in its own time.

Case in point: After I’d handed out the scarves one day, Amelia, who’s one of the youngest in the group of 4-8 year olds, requested for my attention. The music and dancing had already started. At her request, though, I kneeled down so she could whisper in my ear. She inquired politely, “I noticed that Josie has a purple scarf. I’d really like to take a turn with it. May I ask her if she’d trade with me?”

Absolutely, yes.

Josie was just beyond my earshot, but I watched Amelia walk up to her and engage her in a quick and friendly exchange. I watched Josie smile and nod. The girls traded scarves; one smiling because she’d gotten the color she wanted, and the other smiling because she got to help a friend. They worked it out. She shared. Happily. Easily.

I’ve seen this negotiation of “sharing” happen just as often with boys as girls; in dance class and on playgrounds. I could’ve just as easily written this piece about a group of boys working together to build a skeleton from individual x-ray images during science class a few weeks ago. However, it’s less desirable to write about yanking on femurs.

When kids want the same thing at the same time, they can usually work it out. Adults don’t need to interfere. We can trust them to negotiate for themselves, often without any mediation. We don’t need to worry that we’re setting a bad precedent if we give a child something he or she requests.

We don’t need to force so-called sharing or taking turns. Children do it quite naturally most of the time. Policing is far less important than giving them the chance to practice. And when better to practice than in childhood?

* Names changed for privacy.

Trees and lights. Snow and sledding. Family and holidays. For many of us, these are naturally joyful pairs. (Trees and lights are especially exciting if you're a toddler or a cat.)

Of course there's the other side, too. Holiday stress is real for many of us--and it can come crashing down our chimneys with reliable predictability.

Some people hold their breath and just hope for the best, especially if their holiday stress results from spending the holidays with extended family.

According to this Harvard Medical School article, 62% of adults experience "very" or "somewhat" elevated holiday stress levels, partially attributable to family relationships.

After all, family dynamics can be tricky, especially once we have children. Yet, we want our children to experience all the joy that should surround them this time of year, right? Holidays stress doesn't have to be their thing just because it's ours.

Although I won't write about my own holiday stress here because my extended family will read this---I mean, because they're perfect (ahem)---I'll tell you how some people mitigate their anxiety with extended family, especially if All That Togetherness doesn't exactly jingle their bells.

So, what do they do to mitigate the messiness and find joy, instead?

If you're concerned about extended family being a less-than-desirable influence on your kids, find joy and peace in the connection you've created.

If you've parented with the good of the parent-child relationship in mind, then children will naturally gravitate back to the norms of what you've modeled for them.

If you happen to have a child who hangs back at family gatherings, that's perfectly alright. If you're concerned about it, this article about supporting introverted children might help you.

Your kids will join in when they're ready. Let them rest securely in the knowledge that you support their choices and their timing.

For family members who might not understand your child's reluctance to jump right into a big group of people, but who sincerely want to connect with them, you might share ideas like these about how to engage kids without overwhelming them.

Even outgoing kids need support and occasional breaks from the group. Allow them to relax and in your presence, with your full attention. A hug and some verbal support can go a long way.

The more you're there for your kids, the less they'll begin to equate holidays and stress, and will simply find joy in your presence---along with everyone else's.

Many kids love routines and consistency, regardless of age. You can grab your kiddos' usual bedtime story and stick it in your bag if you're visiting relatives out of town.

Odds are good that they'd much rather hear the same story for a few nights in a row than to go without. I call it "Routine in a Box." A few comforts from home will help your child find joy in familiarity, and help you feel merry and bright!

The same goes for touch, even for older kids. If your child normally has a lot of contact with you throughout the day, then he or she will be inclined to crave that and then some (hey, you're their personal lovey!). Stay present. Keep touching.

Obvious, right? Still, somehow, many people go into the holiday stress with extended family as if they were signing up for a hot date in Purgatory. If you find yourself there (with anxiety, I mean, not in Purgatory, because I don't really think that's a thing), give yourself a gold star for each moment you feel peaceful.

Acknowledging and tracking positive feelings among the stressful ones can help you be aware that good things are happening. You can do this, joyfully. Holiday stress and you don't need to share the same strand of lights.

Just like many of us do at home when raising kids, you can take the "pick your battles" mantra on the road, too. It travels beautifully! Things are different now. As the parent of your own children, you get to examine how you were raised.

Engage where you want to. Debate where it's important. This mini-course about what to do when someone you love disagrees with your parenting style can help support you in that.

Ask yourself if you share your extended family's perspectives or have a different take on things. If you observe them, some of your triggers from growing up can offer you insight into your own parenting.

Keeping an open mind can be an incredible gift with psychological benefits, and taking an intellectual approach rather than an emotional one when something bothers you can do wonders for reducing holiday stress. So, you can find joy while you examine your family anew.

More than anything else, be intentional about looking for opportunities to connect and find joy. If Great-Great-Great-Granny's mince pie doesn't do it for you, remember that the cookies are just on the next table over.

Connect with Great-Great-Great Granny over a gingerbread house. Invite her outside to catch snowflakes on your tongues. You might be surprised what she can still do. You, and your kids, will forever cherish the memory.

Holidays and family can, indeed, be a joyful pair, and holiday stress doesn't need to be invited. Our children can see it and be a part of it.

If we've not experienced joy with extended family before, our kids can witness our ability to find it in a whole new way. What a wonderful gift we can give them in allowing them to be part of that.

"Mommy, let's pretend this isn't a train tunnel."

"Okay, what is it?"

"It's a tomb."

Well, hello, conversation stopper. She paused for effect, which is a good thing, because I certainly didn't expect that. After a moment to process and very consciously trust that children's play serves an important purpose for them, I mentally cringed while inquiring, "Is anyone in there?"

"Yep, a dead person."

She smiled lovingly at me, just content to be playing.

I have to admit that this already wasn't my favorite game, and although I didn't know who was inside, I was hoping for some miraculous resurrection of sorts.

"Was it anyone we know?"

"Nope, it's not. It's just some man. He's dead in there."

Well, at least it's no imaginary person we know. Somehow that made it better for me, the adult who should be able to handle a child's imagination.

Still, I waited for the punchline and trusting her play, looking for some clue as to where this was going.

"What happened to him?" I asked tentatively.

"A cow sat on him. And then a car drove on top of the cow."

Well, that would certainly do it. Although she knows bodies stop working when someone dies, we haven't spent much time discussing the specific mechanics of the process.

Then, she added, "Yeah, he was really, really old, like Grandpa Herb."

Click. Now, I see what's happening. Grandpa Herb is actually my grandfather; her great grandfather. As I write this, he's a 95-year-old with a body that's more ready to go than his brain is.

I reminded her that Grandpa Herb is still alive, but she proceeded me to remind me that he's "really, really old and probably won't live much longer."

He might have another decade ahead of him, but he might not. She's bright enough (as kids are) to pick up on pieces of the adult conversations to know that we talk about his life and medical situations differently than we do others'.

Just like we do as adults, kids need to process when change is coming; especially when it's such an abstract concept as this (for all of us). We rarely discuss death with children unless it's necessary, so it's particularly foreign to them when it happens. We can read helpful books like this one and this one (afflinks) to help cover the bases. I can trust that her play is helping her process just as she needs to. And she can ask all the questions she wants to, and I'll do my best to answer them according to our belief system. Of course, I can't tell her what dying is like, though, because it's never happened to me.

So, until then, we find ways to make peace with the unknown. We need to somehow make the intangible, tangible. We need to know that when the time comes, we'll have done something to prepare, because we all want to do something.

Some might call this "game" macabre and make that resurrection manifest somehow, or insist that it's a train tunnel and nothing more. For us, it became a way to process and discuss one of life's Big Topics, using the means my child knows best: learning through play. It's within her power to play; the more she can process it in her own terms without me imposing my agenda on her, the more she can begin to grasp and reconcile the concept. And the more she can be ready for the inevitable, be it for Grandpa Herb or for a goldfish, the less jarring it will be for this child.

Personally, I'm going to beware of sitting cows for awhile. More than that, however, I'll continue to trust that play needs to happen, exactly as it is.

Knowing her grandparents will soon be asking for gift ideas for our daughter, my husband and I decided to take our five year old window shopping today. As usual and as I've written about before, we began with the caveat that although we wouldn't buy anything, we'd take pictures of what she likes so that we're sure to remember. This approach has pretty much been golden for us since she was two, and learning to delay gratification has contributed well to her growth mindset.

Today, however, she was really short on sleep. Even for me, an adult, a lack of sleep thwarts even the very best laid plans. Still, we pursued our endeavor to leave the house.

Upon entering the store, our child uncharacteristically said, "I've decided we're not just going to look at toys. We're going to buy some for me today to take home." I gently and clearly reminded her of our mission. And I hoped for the best.

We made it past the greeting card aisle and into the craft aisle. On display with the crafts, they were selling a sewing machine for kids. She picked it up and announced, "This is what we're buying for me today. Let's go check out now."

I wish I had a dime for every time I'd seen a parent in a similar predicament. I'd be able to buy a thousand sewing machines. Regardless, this was really unlike her.

I acknowledged how much she wanted it and reminded her that we'd put it on her list. I took a picture of it, and for good measure, so did my husband.

She announced that she would carry it through the store with us until it was time to check out, and then we'd buy it. I let her know that she'd be welcome to carry it through the store, but that we'd put it back on the shelf before leaving. Setting expectations upfront usually does wonders for keeping things mutually agreeable. However, the "mutually" wasn't happening here today. So, I presented it as a loving limit and took the time to discuss and validate how she felt.

Sure enough, she chose to carry it through the store, anyway. She had no interest in looking at any other toys. We stopped to look at some decorations and at a few items for my husband, but that was it. She wanted to go no farther, though, so we returned to the craft aisle, the sewing machine still firmly in her grip.

We had nowhere else to be, so we did a bit of emotion coaching to help her. However, it was still a no-go for her. She said she'd wait there "forever" until we bought it. Taking it from her forcefully would do nothing for her emotional intelligence, our connection, or her growth mindset. So we waited, letting her feelings be what they were, and trusting that this was temporary.

After awhile, I asked her to think of a way she'd be willing to leave it at the store. Because she wasn't in an emotional place to think logically right then, I offered her the options of either putting it back right away or walking toward the exit while she held onto it, until we reached the checkout area. At that point, her option would be to hand it to my husband to put back before we reached the door. She chose the latter. And for whatever reason, she quickly put the sewing machine back on the shelf where it belonged. However, she grabbed a unicorn craft that was nearby and held onto it just as steadfastly.

However, near the checkout area, she changed her mind and wouldn't relinquish it. At that point, I shared a story with her about a time when I was little and didn't get a toy I wanted. Her demeanor changed. She softened. For the first time in awhile, she looked me in the eyes and connected. She felt understood.

Shortly thereafter, she offered, "I don't want to put it back on the shelf. I want to put it somewhere...else."

I replied, "It's too hard to take it back to the craft aisle. You want to put it somewhere different."

"Yes. I want to hide it and see if Daddy can find it."

Fortunately, because she's five, her hiding places often include instructions such as, "Please don't look behind the chair."

She looked resolved, proud of having solved the problem herself. All she needed was the time and emotional support to do it. So, off we set on a short mission to find the perfect hiding place for it. After testing a few options, she settled on setting it between the feet of a mannequin. She promptly informed her Daddy not to look there. (Daddy, of course, returned it to its proper place once we were out of sight, and she confirmed later that it was exactly what she'd wanted him to do.)

And off we went to the car; her, sad but accepting, growing in her ability to solve problems. Even among the shiny objects; even when sleep deprived, she found a way to do it that was mutually agreeable. We can both sleep well tonight.

At one of the schools I have the pleasure of visiting regularly, this week's craft table featured what the teacher appropriately called the "paper guillotine," along with some glue and paper. At one point, an unsuspecting adult walked over and saw the setup. She inquired, only half-jokingly, "Oh, is this the table where you slice off your finger and then glue it right back on?" I laughed, albeit a little nervously. I admit I wondered the same thing when I first saw the guillotine. These are four- and five-year-olds using a very sharp tool, after all. However, I trust the kids' teacher implicitly, so if the paper guillotine is out, we go with it (with appropriate supervision).

Every week, I hear adults guide children as well as they can to help ensure their safety and well-being. What troubles me, though, is that despite their unquestionably good intentions, I all too often hear the adults telling the kids what not to do, without further comment or guidance. With all the time I spend in child-focused settings (schools and otherwise), I often get firsthand insight into the kids' experiences.

The "nots" and "don'ts" serve a valid purpose in our adult brains. They convey to our kids what they aren't supposed to do. They also leave me feeling really, well, deflated at the end of the day. And the adults aren't correcting me. They're correcting the kids. What's intended as helpful correction sometimes comes across as criticism and disapproval, and the kids' self-confidence simply can't thrive in that environment.*

To be sure, kids need guidance. They need discipline in the sense of "teaching," along with clear boundaries. And they need support while they figure out what we adults expect of them. Janet Lansbury, early childhood expert, writes extensively about the different forms boundaries take and how to navigate them with your kids, while building their self-confidence. Although she often writes about toddlers, the concepts she unpacked for me in this life-changing book still apply long after toddlerhood (afflinks). This is another great book that's full of practical suggestions and real-life scenarios.

That said, the tricky part is that just by virtue of being kids, they're, um, new here. To Earth. Their brains are still figuring out all sorts of things the rest of us have known for awhile. And in their defense, while many of them can and do understand what not to do, they still need help connecting the dots to what they should do, instead. Even school-age children have only been in school for a short time, and they're still figuring out how the rules and communication styles differ from person to person; classroom to classroom.

And in almost all the places where I see adults (both teachers and parents) interacting with children, I see all sorts of completely avoidable emotional strife. If we adults tweak our approach just a bit, it can remove any doubt in the child's mind about what we really want from them, while helping grow their self-confidence. We can make life easier for them and for ourselves. Who wants unnecessary conflict, anyway?

Here's what I've seen some of the best adult-leaders (teachers and parents) do that works beautifully. As the mother of my own child, I'm trying to emulate these concepts.

Every time you feel a "don't" or a "stop" message about to come out of your mouth, replace it with the opposite, positive statement. Rather than "Don't push," try, "Please keep your hands to yourself." If it helps you practice until it comes naturally, you can add the "do." Example: "Please do keep your hands to yourself." Instead of, "Stop throwing papers on the floor," try, "Please keep papers on the table." "Please walk" is just as easy to say as "Don't run," but the emotional tone is much more empowering. The child will know exactly what to do.

It's amazing how much less defensively kids (and, ahem, adults) respond when they're given positive instructions rather than directives that imply they're about to misbehave, even when they're doing everything right. From what I've witnessed, it makes a huge difference in the tone of the room, be it a classroom or at home.

A common pitfall I observe is when adults get the positive wording right, but then they attach a threat or consequence to it. For example, "Keep the crayons in the box or I'll have to take them away." Unfortunately, this approach strengthens kids' self-confidence no better than negative instructions do. Both activate the same part of the brain that signals danger, and it's hard to thrive that way. An example of what would convey the same message without the threat would be, "The crayons are for later, so please leave them in the box. First, it's time for a story."

I love it when I hear an adult call out kids who are doing something right. The catch here is to avoid indirectly shaming the kids who aren't doing it right, but rather, to build trust that we see kids in all their goodness. I love hearing, "Hey, I noticed how everyone in the class was quiet while I was explaining our activity today. I really appreciate that." Or, quietly to a child in the classroom, "Matty, I noticed you kept your hands to yourself today. Thanks for doing that." Alternatively, at home, "Thank you so much for cleaning up your spill without me asking you to do it! You sure do know how to help around here. I appreciate you."

I love how kids glow when they hear that they're getting things right.

In the class with the paper guillotine, what worked beautifully was this: "This tool is really sharp. The only thing that can go under the blade is paper. Keep your fingers out from under it when you push down on the lever." I'm happy to report that no fingers or other appendages became victims of the paper guillotine that day. All of the kids knew exactly what to do with the tool, because they'd been told what to do with it. We took the time to clearly and positively instruct them. Everyone who tried it appeared to find it fascinating, and dare I say, fun. Every single one of the kids went in giving the machine the side-eye, but knowing what to do, their self-confidence grew when it worked.

Raising our own children can be a lot like that: seemingly kind of scary at first, but when everyone figures out what to do, life can really go quite smoothly. The more we practice positive parenting, the more our confidence in the process can grow. And with peaceful smiles on our faces, we'll watch our kids' self-confidence soar.

________________________________________________________________________

*Source: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/compassion-matters/201106/your-child-s-self-esteem-starts-you