Sign in

Don't have an account with us? Sign up using the form below and get some free bonuses!

In positive parenting, the power of a hug is some of the best preventative medicine that exists for the adult-child relationship, even with children who aren’t our own.

A girl I'll call Juniper, who was then two and a half years old, was standing with my child and me in the doorway just before we joined Teacher Tom for outdoor story time. It was the very first time I'd ever met her. I was the last adult chaperoning kids out of the building, so I couldn't join story time with my child until I was sure all the kids were accounted for. Juniper had no intention of joining us, though, as I could clearly see from her body language. As Teacher Tom noticed my child and me waiting in the vestibule, he beckoned for us to join him. A lot of people were waiting for us. He was unaware that I was encouraging Juniper, who was cowering in a corner, to follow us.

In an attempt to connect with Juniper, I crouched down to her level and reached out my hand. I'd have held her hand, hugged her, or picked her up, if she'd indicated any of those options were acceptable. To my surprise, however, she jumped at me like a mini-superhero, then started throwing punches and kicking me. She tried to bite my arm. Holy moly.

Despite being momentarily stunned, I heard myself think, "I'm going to Janet Lansbury this." (I didn't know Janet was a verb. I always thought she was an early childhood expert.) As calmly as I could muster despite Juniper's flailing limbs, I held her shoulders at a safe distance from my body. I looked her in the eye and said, "I won't let you hurt me. I'll help you through this." Immediately, she calmed, took a final halfhearted swing at me, and took off running down the hallway of the building. Knowing I couldn't leave a child alone in there, I invited my child to follow me as I gently pursued Juniper. I gave her plenty of space.

To be clear, I use positive discipline as a synonym for teaching. I don't support force or punishment of any kind as a parenting approach. In my experience, a hug and almost any form of positive parenting go so much farther than anything punitive.

Before I continue with what happened, it’s helpful to understand some of the different approaches I could’ve taken, based on different parenting styles. This child didn’t need to be mine for the same neuroscience to apply.

If I acted like an authoritarian parent, it likely would've presented as me yelling after her, catching her, and picking her up against her will. Flailing or not, I'd plop her down into to story time. Traditional authoritarian parenting (the most commonly punitive option) centers around adults controlling children. It has negative long-term consequences for the parent and child relationship, as well as for the child

herself, as John Gottman, Ph.D. describes in Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child (afflinks). Forced compliance does nothing to support children’s emotional intelligence or attachment to their caregivers, and I certainly wasn't going to make this little stranger "behave" somehow.

On the opposite end of the parenting style continuum from authoritarian parenting is permissive parenting. However, Dr. Gottman, Janet Lansbury, and many other experts caution that permissive parenting isn't the antidote to authoritarian parenting. It, too, carries risks for the child. Children need loving and reasonable limits to feel secure. Permissive parenting might’ve looked like my letting Juniper run wherever she wanted, and not saying a word to her about it.

Neither approach would've given Juniper helpful tools upon which to rely in the future. Moreover, if she happened to be a highly sensitive child (HSC), odds are good that anything punitive might have sent her into an even tougher emotional situation.

This balanced type of positive parenting is called authoritative parenting. Note that although the name authoritarian parenting, which is negative, sounds like authoritative parenting, the latter is positive.

In any case, this certainly wasn't the time for a sticker chart or a "red behavior card,” which is common in many preschools. (I'd argue that no time is right for those, but that's another post.) As Ross Greene, Ph.D., argues in The Explosive Child, "...The reason reward and punishment strategies haven't helped is because they won't teach your child skills he's lacking or solve the problems that are contributing to

challenging episodes..." These methods don't teach children how to cope when they're emotionally overloaded.

Conversely, positive parenting is linked with better long-term outcomes for the child. This is true not only short-term, but also for the child's long-term wellbeing (1). Examples of positive parenting styles include RIE® (2), attachment parenting, authoritative parenting, and many others. Descriptions are readily available on the Internet, and my website has a list of my favorite positive parenting books. (Yep, I've read everything there. I share only the ones that have solid, actionable messages and that promote positive parenting.) I wish I had a dollar for every style of parenting in the dictionary these days, but truthfully, the names don't matter much.

All that said, I wasn't entirely enthusiastic about pursuing this small Mike Tyson. However, I realized that this responsibility was on me even if I didn't sign up for it.

I trusted that I was there for a reason. I needed to find that middle ground that would help Juniper trust that I was on her side while still accomplishing what we needed to do: reconnect with the class.

So, I offered her a hug. Totally bewildered for a moment, she yelled, "No!" And then she sucked her thumb, rocked herself, fell to the floor crying, and then got up and ran at me again. For a moment, I almost blocked my body for safety. I saw something different in her eyes, though, so I stayed within reach. She ran to me as if I were a long lost friend and collapsed into my arms, bawling her little eyes out.

She hugged and hugged and hugged, leaving my daughter and me surprised, but on we went hugging. Her tension melted away entirely. We proceeded to story time peacefully.

At that point and for reasons unbeknownst to me at the time, I told her that I have a "hug button" on my shoulder. Anytime she'd need one, she could come and touch my shoulder, and I'd know what to do. I made sure to always crouch down when she came near, just in case she needed to push it.

If any child were to put something unsafe in her mouth and start running down the hill on the playground, it was her. With some false starts, I learned that following her and asking her to remove the choking hazard would backfire. It was all the convincing she needed to keep the aforementioned item there. When I pushed too hard or sounded forceful, fearing for her safety, she’d take off running and create an even greater safety risk to herself.

Once I realized that, I chose to address her potential issues proactively. The moment I saw her put something in her mouth, I'd crouch down and call her name from wherever I was on the playground. I'd stay put. She'd look over, and I'd point to the invisible hug button on my shoulder.

More often than not, she'd nod and come running my direction (sometimes with the aforementioned object still in her mouth, but it was progress). She'd hug me for as long as she needed and then relinquish the item.

Except for when she didn't come. I'm not perfect (more like a million miles from it), and sometimes my tone would be too worrisome for her. Or sometimes I'd think I'd done it "right," but she was too emotionally overloaded to connect.

I lost count of how many times a proactive hug completely deescalated potential problems. I'd see a "look" on her face that signaled trouble, so I'd offer a hug. And just like magic, all was right with her world again. Some of the other kids in class even joined in on the “hug button” initiative.

On the last day of class, Juniper walked up to me and offered me a hug for the first time, proactively. She'd never done that before. I happily accepted. Much to my surprise, she cupped my face in her little hands and she whispered, "I love you." It was the perfect 2.5-year-old translation of "Thank you for understanding exactly what I needed when I didn't have the words to explain it."

And I love her, too, in the most wonderful way of loving a small person I'll likely never see again. She helped show me the power of positive parenting from a lens outside that of my own family. She reinforced that it's better not to chase my child; but instead, to be rock solid and a "safe place" emotionally. She confirmed what the the gentle parenting books say should happen when a child feels connected. My own parenting is better for the important positive parenting lesson she taught me.

There's a lot to be said for the power of a hug.

_____________________________________________________________

Source (1): https://www.parentingscience.com/authoritative-parenting-style.html

Source (2): https://www.rie.org/educaring/ries-basic-principles/

I hope he doesn't remember this, but the first time I met Teacher Tom, I was a bumbling idiot.

Now, here's why it's particularly embarrassing. You see, because my mom was in the entertainment industry while I was growing up, I had exposure to more than my fair share of celebrities.

Then, as an adult, I just kept running into them. For instance (and to my surprise), Steven Tyler once approached me and asked if he looked alright; he'd had only a quick cold shower and had to hurry, and was feeling self-conscious. I responded to him and we spent 45 minutes having a one-on-one conversation before he introduced me to the rest of Aerosmith. (He's a super nice guy, for what it's worth. I felt awkward ending the conversation, as if I should invite him to lunch or something.) I hadn't been looking for him or any of the other famous people I've stumbled across; it's one of those funny things that has just kind of happened with some degree of regularity throughout my life. It's always been my opinion that they're just people, so why get so worked up about them?

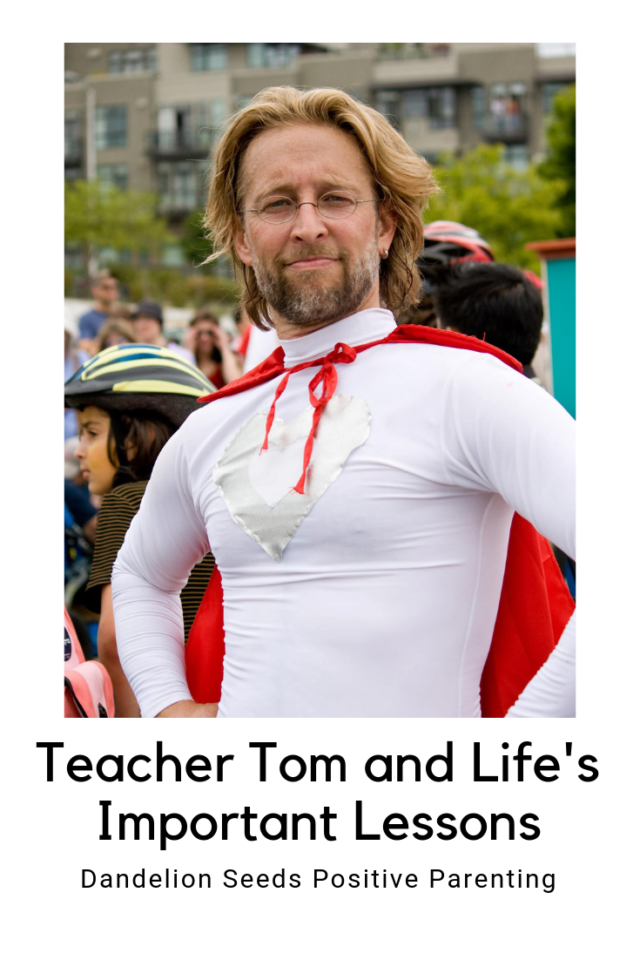

My life continued as it had, and one day while walking down the street with my daughter near downtown Seattle, Washington, I looked up to see a playground adjacent to an old church. On it, kids were playing. The teacher was the one who caught my eye, though---and he looked familiar. I racked my brain for a moment and realized it was, indeed, Teacher Tom (otherwise known as Tom Hobson) of Woodland Park Cooperative School. Known worldwide in the respectful parenting community (and beyond), he's hailed by parenting experts as one of the “world’s leading practitioners of ‘democratic play-based’ education." He's also a heck of a good writer. I'd recognized him from his blog about early childhood education (and other related topics).

I didn't know he'd be right there. And for the first time in my life, I completely geeked out in front of someone---and that someone wasn't a rock star or movie star, but rather, a preschool teacher. My subconscious enthusiasm did all sorts of unconscionable things: I stuttered, used the wrong word more than once, and despite my efforts, just couldn't seem to "pull up" conversationally. I guess I'm a sucker for intelligent people who do important work on behalf of children.

He engaged my introverted daughter as best he could and invited us to join his class sometime. We accepted his invitation. I enrolled my child for the following summer and the school year thereafter.

By spending a year working in his classroom every week, I got to know him much better than I did when I first wrote about him. I'll stand behind what I wrote then---he's still simultaneously on the kids' level while also being a strong and respectable leader. He's intriguing. Even my husband can't quite put his finger on it. He agrees, "There's just something special about him."

Beyond what he does to entertain the kids, he also really engages with them.

Unlike many of us, who are often inclined to multitask or think about the "next responsible thing we need to do" while playing, he really gives the kids his undivided attention. He's all in. What I observe in their response is that they feel important in his presence (because they are). There's a critical parenting lesson in that.

You won't find a single worksheet anywhere in his classroom (other than, perhaps, as scrap paper). The most formal instruction I ever heard him offer to the class was, "Here's something you need to know in life: no one wants you to mess with their glasses, their hat, or their hair. Nobody likes that." (He's right.)

Within the context of the inevitable and occasional conflict that comes up amongst the children, he helps them navigate their challenges peacefully. With him, it's safe to talk about feelings; in fact, he spends a fair amount of time talking about them. He reads about them. I'd surmise that every kid in his class graduates with a better understanding of humanity than many adults have.

I'd be surprised if the adults who spend time with him don't come away as better parents and partners than they were before observing him with the kids.

Today, our last day, the kids put on an end-of-year play as part of their "graduation" ceremony. While Teacher Tom was coaching them beforehand---and before the audience entered the room---he advised the kids that sometimes, unplanned things happen during performances. People drop their props and whatnot. If one of those unforeseen things were to happen, he advised them to keep performing, citing the old cliché---"the show must go on."

They performed. Most things went according to plan and the play went beautifully. Families celebrated, and then the kids crossed the stage one at a time to symbolize their leaving Teacher Tom's class to move on to new endeavors.

My guess is that we all walked away feeling somehow changed, likely for the better, for his presence in our lives.

I didn't mean to meet Teacher Tom any more than I'd planned to hang out with Aerosmith. One of those encounters was fairly cool (much cooler than I've ever been, for sure); the other, made a difference.

There's a hole in our hearts tonight after finishing our time with Teacher Tom. And yet, that hole is full of a lot of teaching that I'll still be processing, and trying to implement as a parent, for quite some time.

I'd sincerely like to thank him for the work he does. Not only do I want to thank him for what he writes to keep the rest of us in check every day (although I don't think that's his goal); I also want to thank him for opening his heart to these kids.

He loves them. And every single one of them feels it.

And now, we move onward---better than we were before we met him, because, as he said, the show must go on.

Most kids have inherently good negotiation skills. Pull out a chocolate bar and tell kids to divide it up for themselves, and you'll find quick proof of that. When it comes to conflict resolution and self-regulation, however, many adults wonder whether children possess the emotional intelligence and executive functioning skills to navigate that territory. As a result, many grown-ups are quick to intervene and solve social problems for them. After all, emotions are tricky even for us to manage, so it's tempting to guide our kids when we sense trouble. I know because I've done it.

I'll share an example of how much better it can work when kids figure out how to resolve conflict for themselves, however. When I was in a play-based science class with a group of four- to six-year-olds last week, they made "squishy circuits," where they connected two sets of wires, Play Dough, and mini-lightbulbs to the positive and negative ends of batteries in a particular sequence. If they connected everything correctly, the lightbulbs would light up.

Adults were there to help ensure the kids' safety, of course. (Personally, I'm thankful for observing Teacher Tom in action at another school I visit weekly. He's a world renowned teacher at a play-based preschool in Seattle. He's helped me chill considerably about what I consider dangerous for kids, and he facilitates conflict resolution better than any teacher I've ever seen.)

Once the kids got the hang of basic circuitry, they could get as creative as they wanted with their Play Dough inventions. One five-year-old girl who I'll call Catherine, who regularly displays high emotional intelligence and emotional self regulation, announced that she was going to use her Play Dough to make a kitty with a water bowl. Often demonstrating strong executive functioning skills, she's a "stick to the plan" kind of kid. (Executive functioning includes things like self-control, planning, and the ability to remember instructions. If you're looking for a deeper understanding of executive functioning and self-regulation, this article from Harvard's Center for the Developing Child describes them well.) So, she set to work right away while most of the other kids rolled their materials around haphazardly, deciding what to make.

After about 10 minutes, the girl next to Catherine, another five-year-old I'll call Mia, reached over and demolished Catherine's kitty. I've observed that Mia sometimes lacks the executive function skills to self-regulate. Looking flabbergasted, Catherine called me over to help resolve the conflict, announcing matter-of-factly what Mia had done. It was obvious. Catherine's blue Play Dough that Mia squashed was still in the center of Mia's palm. Mia had been using green.

Before I could say a word, Mia announced loudly, "I didn't do anything wrong!"

I felt tempted to call Mia out on her transgression and show my frustration. My first impulse was to ask her what the heck she was thinking. (I'm still learning and have to catch myself, too.) However, I know an objective tone is more helpful for encouraging honest dialogue. So, I took a breath and stated neutrally to both of them, "It sounds like something happened here." Mia has older siblings at home, and I know she's no stranger to managing conflict situations. I can't say with certainty, however, where she is on developing her executive functioning skills.

Dealing with conflict is a hard life skill to learn, because frankly, negative emotions are hard. I'm an adult and I still don't like conflict. We're not "wired" to like it. However, the ability to recognize someone else's point of view goes a long way toward developing emotional intelligence and self-regulation.

So, I continued.

Me, in a curious and non-accusatory tone: "Mia, I observe blue Play Dough in your hands. I'm feeling curious about that."

Mia: "Well, I did squash her kitty, but she had just started working on it. She didn't care."

Catherine: "I didn't just start working on it. I had been working on it the whole time! It was important to me."

Me: "Hmmm. Catherine, I hear you saying that it was important to you."

Being an active listener, including playing back what you've heard, is a key ingredient in helping kids resolve conflicts. It shows that you're internalizing what they said, and essentially invites them to continue while feeling supported. Accusation is counterproductive; only when kids feel supported can they grow their emotional intelligence effectively.

And as is true with many things, when it comes to engaging in kids' conflicts, less is more. Less adult talking is more beneficial to kids learning to solve problems on their own. When they feel capable of doing that, it reinforces growth in the self-regulation and executive functioning parts of their brains.

Catherine and Mia continued without prompting.

Catherine, addressing me: "I really didn't feel so happy when she did that."

Mia, to Catherine: "No, you were happy."

Catherine: "No, I really didn't feel so happy when you did that."

Mia: "Oh." Mia's eyes went downcast then with apparent remorse, and perhaps with understanding the deeper connection between emotions and behavior.

At that point, they sat together silently, in what seemed to be somewhere between an impasse and emotional connection. I paused for long enough that I was sure each had finished saying her piece. When neither continued, I suggested next steps without solving anything for them, similar to creating a negotiated agreement in a boardroom.

Me: "I'm going to guess that nobody in the room likes getting their Play Dough squashed. I'm wondering if that's true."

Both girls, agreeing: "Yeah. No one should squash Play Dough."

Me: "Okay, then. I think you've solved a problem. Since no one likes getting their stuff squashed, I wonder if we can agree not to squash anyone else's stuff, either." (I essentially played back the solution they'd reached, just broadening it slightly.)

Both girls, nodding vigorously: "Yeah. Let's do that. No squashing people's stuff!" I could almost see the self-regulation synapses connecting in Mia's brain. Moreover, Catherine's emotional intelligence was growing by having expressed her frustration in an appropriate way. She felt "heard" and could move on. Her emotions had no reason to escalate. Executive functioning in action.

All of us: Exhale. Resolution. Consensus.

Both girls seemed resolved in the matter. Their conflict was now water under the bridge. They moved forward happily with their projects.

I fully trust that their self-identified conflict resolution did far more for their executive functioning skills than any punishment or forced apology could have.

And the sooner we let them try, the better. Studies show that practice between the ages of three and five is particularly beneficial. This is also the age that their working memory develops in leaps and bounds, so that they'll have specific experiences upon which to draw as they get older. Areas of the brain that develop during this timeframe are profound and substantially important for future interactions. Some would argue that the ability to self regulate and strong emotional intelligence skills matter far more than IQ alone.

Socially skilled kids can focus attention on managing conflict and growing their relationships with peers. It's possible because they already have the emotional intelligence and self-regulation tools in place to do those things. Conversely, those with executive functioning issues need more practice. The adults in their lives will support them best by resisting the urge to dive in and rescue them when they see any type of conflict; but rather, by letting them attempt their own conflict resolution, even if they get it wrong. Practice makes perfect, right? Our presence is beneficial and sometimes necessary, but our words should be few.

Maybe emotions are tricky for adults to manage because some of us didn't get enough practice when we were kids. I don't know. What I do know anecdotally, however, is that emotionally intelligent kids usually grow up to be emotionally intelligent people (adult-sized, because, of course, kids are people, too). The ability to understand and manage emotions, resolve conflict, and display emotional intelligence is a lifelong gift to ourselves and those around us.

_____________________________________________________________

Follow Dandelion Seeds Positive Parenting and Dandelion Seeds Positive Wellness on Facebook. We’re also on Instagram at DandelionSeedsPositiveLiving.

We appreciate your support! Click here to see all the children’s books, parenting books, toys and games, travel necessities, holiday fun, and wellness-related items that we’ve used and loved. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. However, pricing (including sale prices) and shipping are still from Amazon. Once you click the checkout button from your Dandelion Seeds cart, it’ll direct you to Amazon to complete your purchase.

Although I was on the other side of the playground when it started, I suspect the conversation began something like this: "Hey, let's see if you can throw the football so hard that it gets stuck in the tree!" Perhaps having never experienced the frustration of getting a ball stuck up high, this young boy saw an opportunity to try something new.

Most of us have wished for the lost moments of our life back when we were working to retrieve an irretrievable item. As a result, most of us have made an unwritten rule that we should never throw something up there intentionally.

But not this boy.

Fortunately, his muse (who happens to be his teacher) is often game for challenging long-held beliefs--especially the ones that adults have imposed on kids, often without good reason. Rules for rules' sake, you know. "The way we've always done things."

By the time I arrived, they were drawing a crowd. We watched our impromptu quarterback throw the ball upwards toward the high branches. It's amazing how hard it is to get a ball to stick in a tree the one time you want it to stay there!

With some effort, but not too much, he threw the ball high enough. And it stuck, way up there. Right where the boy wanted it. Everyone rejoiced in the victory we all wanted.

We found joy in breaking a rule about how things "should" be. At least I did. It felt wonderful to do something differently than many would, just because we could. On some level, we found freedom in it.

We get to switch things up. We get to examine the rules we consciously hold because they've always been that way. Perhaps our parents raised us perfectly; gently; respectfully. It's good to emulate that in all the ways we can. Or perhaps they didn't, and now, with our own children, we can challenge our long-held beliefs about parenting. We get to break negative cycles. It's important to do that, too.

Sure, some rules make good sense; I'm not suggesting we throw our belongings into trees. Still, along with the rules we know we have, we can catch a glimpse of the ones we didn't even know we were holding. Maybe we reconsider a "truth" we have about discipline, boundaries, or the innate goodness of children.

In examining these things, we regain the same type of freedom that the boy unleashed for us by wanting the ball in the tree. We get to do things our way, even if they're different from what our parents and friends have done with their kids. We get to make our own rules, tossing out our parenting "shoulds" and replacing them with, "Sure, let's try that."

Having this freedom in parenting is not only a gift to our kids, but it's a gift to ourselves, too. Once we know the rules that don't serve our families well, we get to launch them as high and as far as we dare. And they can stick there, never returning.

There's incredible freedom in letting go.

At one of the schools I have the pleasure of visiting regularly, this week's craft table featured what the teacher appropriately called the "paper guillotine," along with some glue and paper. At one point, an unsuspecting adult walked over and saw the setup. She inquired, only half-jokingly, "Oh, is this the table where you slice off your finger and then glue it right back on?" I laughed, albeit a little nervously. I admit I wondered the same thing when I first saw the guillotine. These are four- and five-year-olds using a very sharp tool, after all. However, I trust the kids' teacher implicitly, so if the paper guillotine is out, we go with it (with appropriate supervision).

Every week, I hear adults guide children as well as they can to help ensure their safety and well-being. What troubles me, though, is that despite their unquestionably good intentions, I all too often hear the adults telling the kids what not to do, without further comment or guidance. With all the time I spend in child-focused settings (schools and otherwise), I often get firsthand insight into the kids' experiences.

The "nots" and "don'ts" serve a valid purpose in our adult brains. They convey to our kids what they aren't supposed to do. They also leave me feeling really, well, deflated at the end of the day. And the adults aren't correcting me. They're correcting the kids. What's intended as helpful correction sometimes comes across as criticism and disapproval, and the kids' self-confidence simply can't thrive in that environment.*

To be sure, kids need guidance. They need discipline in the sense of "teaching," along with clear boundaries. And they need support while they figure out what we adults expect of them. Janet Lansbury, early childhood expert, writes extensively about the different forms boundaries take and how to navigate them with your kids, while building their self-confidence. Although she often writes about toddlers, the concepts she unpacked for me in this life-changing book still apply long after toddlerhood (afflinks). This is another great book that's full of practical suggestions and real-life scenarios.

That said, the tricky part is that just by virtue of being kids, they're, um, new here. To Earth. Their brains are still figuring out all sorts of things the rest of us have known for awhile. And in their defense, while many of them can and do understand what not to do, they still need help connecting the dots to what they should do, instead. Even school-age children have only been in school for a short time, and they're still figuring out how the rules and communication styles differ from person to person; classroom to classroom.

And in almost all the places where I see adults (both teachers and parents) interacting with children, I see all sorts of completely avoidable emotional strife. If we adults tweak our approach just a bit, it can remove any doubt in the child's mind about what we really want from them, while helping grow their self-confidence. We can make life easier for them and for ourselves. Who wants unnecessary conflict, anyway?

Here's what I've seen some of the best adult-leaders (teachers and parents) do that works beautifully. As the mother of my own child, I'm trying to emulate these concepts.

Every time you feel a "don't" or a "stop" message about to come out of your mouth, replace it with the opposite, positive statement. Rather than "Don't push," try, "Please keep your hands to yourself." If it helps you practice until it comes naturally, you can add the "do." Example: "Please do keep your hands to yourself." Instead of, "Stop throwing papers on the floor," try, "Please keep papers on the table." "Please walk" is just as easy to say as "Don't run," but the emotional tone is much more empowering. The child will know exactly what to do.

It's amazing how much less defensively kids (and, ahem, adults) respond when they're given positive instructions rather than directives that imply they're about to misbehave, even when they're doing everything right. From what I've witnessed, it makes a huge difference in the tone of the room, be it a classroom or at home.

A common pitfall I observe is when adults get the positive wording right, but then they attach a threat or consequence to it. For example, "Keep the crayons in the box or I'll have to take them away." Unfortunately, this approach strengthens kids' self-confidence no better than negative instructions do. Both activate the same part of the brain that signals danger, and it's hard to thrive that way. An example of what would convey the same message without the threat would be, "The crayons are for later, so please leave them in the box. First, it's time for a story."

I love it when I hear an adult call out kids who are doing something right. The catch here is to avoid indirectly shaming the kids who aren't doing it right, but rather, to build trust that we see kids in all their goodness. I love hearing, "Hey, I noticed how everyone in the class was quiet while I was explaining our activity today. I really appreciate that." Or, quietly to a child in the classroom, "Matty, I noticed you kept your hands to yourself today. Thanks for doing that." Alternatively, at home, "Thank you so much for cleaning up your spill without me asking you to do it! You sure do know how to help around here. I appreciate you."

I love how kids glow when they hear that they're getting things right.

In the class with the paper guillotine, what worked beautifully was this: "This tool is really sharp. The only thing that can go under the blade is paper. Keep your fingers out from under it when you push down on the lever." I'm happy to report that no fingers or other appendages became victims of the paper guillotine that day. All of the kids knew exactly what to do with the tool, because they'd been told what to do with it. We took the time to clearly and positively instruct them. Everyone who tried it appeared to find it fascinating, and dare I say, fun. Every single one of the kids went in giving the machine the side-eye, but knowing what to do, their self-confidence grew when it worked.

Raising our own children can be a lot like that: seemingly kind of scary at first, but when everyone figures out what to do, life can really go quite smoothly. The more we practice positive parenting, the more our confidence in the process can grow. And with peaceful smiles on our faces, we'll watch our kids' self-confidence soar.

________________________________________________________________________

*Source: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/compassion-matters/201106/your-child-s-self-esteem-starts-you

For the past week, I've attended a multi-age outdoor school led by Teacher Tom, who's hailed by parenting experts as one of the "world’s leading practitioners of 'democratic play-based' education."* If you haven't followed his blog or bought his book, you should, and if you can attend his class, even better. Although I exceed the age limit for his class (wait, I don't look 5?), the cooperative model mandates that I spend at least some time working there while my child attends. Since my child wants me to stay at school all the time and it's too far for me to drive home while she's in class, and because I like it there, I stay. All good.

If you know anything about him (or if you don't, now you will), it's that he spends a lot of time observing and engaging with the kids. As an observer myself, it's easy to see how this role suits him. But what does observing Teacher Tom have to do with gentle parenting? Nothing, directly. Besides, he doesn't fit the "gentle parent" poster image some people have in their heads. He's not all hugs and feel-goods. As far as I can tell, he doesn't even shave his face every day (isn't that in the rule book?). So, if he's not raising your kid (and he's not), what does he do that's so special or different that it warrants your attention? Here's what I've witnessed:

He "gets" them and speaks their language. On the first day of class, he picked up a tiara from the playground dirt (where most of the valuable jewels are kept) and put it on his head. A little girl pointed out that he was wearing it backwards. He fixed his error, and shortly thereafter, someone tried to yank it right off him. My adult brain assumed he'd relinquish it (adults are polite, right?), but instead, he respectfully claimed ownership of it and wouldn't share. He wasn't done with it yet.

Without any lecture or adult-infused words about taking turns, he ingratiated himself as one of their tribe by doing what many of them would've done. I wondered if his refusal would be off-putting to the kids, but instead, he'd built credibility. He taught fairness without having to "teach" a thing. Many of us fall victim to playing as adults play: borderline fun, but kind of hung up on enforcing rules. We manufacture "teachable moments" and do our best to stay clean. If building connection is your gentle parenting goal, just look at this guy and the way kids flock to him (I've dubbed the kids his Merry Band of Followers). We take ourselves far too seriously.

Teacher Tom reminds us that we have our kids' permission to act like actual kids.

Red cape or not, I've seen Teacher Tom leap over a tall play structure in a single bound and break up a heated altercation between young boys. To the extent that he plays like the kids do, he's also clearly in charge. He sets limits and holds them unapologetically. Fairly. Respectfully. He's firm without shaming or creating guilt. He corrects behavior immediately when he witnesses a transgression, and then like water off a proverbial duck's back, he goes on playing. There's no room for grudges. They're counterproductive. In following through with his limits without waffling, he builds yet another kind of credibility.

Kids know they can trust him to help when they need him. They don't wonder whether he's a reliable leader; they know he is. As gentle parents, it's easy to second-guess the limits we set in the tough moments and come off as wishy washy. However, no one thrives on shaky ground. Without sacrificing kindness, Teacher Tom reminds us that it's okay to be firm and direct. And then move on.

Teacher Tom challenged the kids to fill a large open canister on wheels, which was at the top of a small concrete hill, with water. Then, they'd experiment to see what would happen when they released it. The kids obliged, lugging bucketful after bucketful of water up, up, up to Teacher Tom, who was sitting most of the way up the hill. He emptied their buckets into it. Once it was finally full to the brim, Teacher Tom counted down for the Big Release. We all waited with eager anticipation. As quickly as the water-filled canister started picking up speed, it stopped just as suddenly,

catching on something, and proceeding to launch aaalllllll the water directly onto him. He was drenched in dirty playground water. His response: "That. Was. Awesome." And he laughed from his belly, just as amused by the surprise ending as the rest of us. He instinctively saw the situation from the kids' point of view; there was nothing to reprimand. What a great reminder that we're teaching our kids how to react when things don't go as planned; what a great way to model resilience.

catching on something, and proceeding to launch aaalllllll the water directly onto him. He was drenched in dirty playground water. His response: "That. Was. Awesome." And he laughed from his belly, just as amused by the surprise ending as the rest of us. He instinctively saw the situation from the kids' point of view; there was nothing to reprimand. What a great reminder that we're teaching our kids how to react when things don't go as planned; what a great way to model resilience.

Before I met Teacher Tom, I didn't know whether to expect him to be some combination of Superman and Mary Poppins (would he wear the cape and have the magical flying umbrella?), or if I expected some Dad-Gone-Rogue-Who-Never-Left-The-Playground. What I observed, though, is that while he's kind of those things, he's foremost really quite human. And you know what, gentle parents? That's really what your kids need most—the ability to see you as a real, true, reliable, flawed, predictable, and regular person who, with any luck, continues to put kindness first.

_____________________________________________________________

To see all the child- parenting-, travel-, and cooking-related items that have stood the test of time in my house, including my favorite books, click here. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

There's a little boy in Teacher Tom's multi-age summer school whose name isn't Jimmy, but I'm saying it is to protect his privacy. Jimmy is quite little, as in, he still has to wear a sticker on his back that reads, "Please take me to the bathroom at 2 p.m." He can't be any older than his potty checking time. However, he's surrounded by older kids who don't need stickers on their backs; they've more experience with such things.

Jimmy had been working for almost two weeks to figure out how to climb into the tire swing. It's plenty short enough for him, but by virtue of being a tire swing, it not only sways but also spins when he touches it. Tricky.

Well, today, he succeeded in climbing in by himself for the first time. He looked incredibly proud. However, he immediately encountered a new problem. How would he make it go?

In this new conundrum, he called to Teacher Tom as one would: "Push." He was soft spoken and polite about it; somewhat bewildered to find himself with another new challenge so soon. He'd achieved step one but knew that someone had to do something more.

In response, Teacher Tom warmly yet factually replied, "That swing isn't moving." And he stayed right where he was, watching Jimmy. Now, this is the really tricky part. If Teacher Tom were to respond to every request for a push / a pull / a whatever-it-is, he'd have to be in about 20 places at once, rather than doing his job. Of course he helps kids in need; that is his job. But he doesn't always help them in the way they ask. Sometimes, his best teaching tool is simply waiting to see what the kids can figure out.

In this case, by giving Jimmy his full attention and acknowledging his request for a push, Jimmy likely felt heard. What happened next, though, was an unexpected plot twist.

By not jumping to Jimmy's aide as many would, he opened a door to greater possibilities. Indeed, Jimmy succeeded in conveying his message. What also happened is that another student who's name (isn't) Kate—a highly sensitive child who's disinclined to engage with other kids, and who liberally applies what some would call selective mutism—well, she heard the request, too. To the surprise of those who know her, she piped up, "I can push you, Jimmy!" And to his rescue she came. She helped that little boy swing for a good ten minutes.

So, yeah, Jimmy got the push he desired. Jimmy was happy for climbing in, in the first place. That was his victory. What also happened, perhaps more notably, is that Teacher Tom's "wait and see" approach facilitated very natural cooperation and fostered community among the children.

Kate, a child who wouldn't normally jump into a social scene, saw an opportunity to not only connect in a way where she felt safe emotionally, but also to lend a hand. In doing so, she proved to herself that she could. My guess is that the message will stick with her and manifest in other positive ways throughout her week, and perhaps much longer.

Now, there were two distinctly proud smiles on the playground; one from a child who was swinging high after a mighty climb, and one from a child who got to demonstrate her bravery in a new and unexpected way.

Sometimes the hardest thing we can do, as a parent, is wait to see what happens. And sometimes our kids' best confidence comes from being given the opportunity to grow.

After finishing a two-week, multi-age summer class with Teacher Tom, who's an internationally respected teacher and writer, I asked my child what she thought he was really good at. She pondered my question for a moment and thoughtfully replied, "He's really good at sitting."

Well, shoot. At the risk of bragging, I'm a fine sitter, myself. Now that I know it's Teacher Tom's greatest strength (in her mind), I feel compelled to up my sitting game. Would any of you be up for a sitting challenge, or perhaps agree to be my sitting accountability partner?

The thing is, she's right, but in the most complimentary of ways. Case in point: Jimmy, about whom I’ve written before. His name isn't Jimmy, but I'm saying it is to protect his privacy. He's two.

Teacher Tom showed a broken tricycle to Jimmy and a bunch of other kids. Its seat had long since gone missing, leaving nothing but a flat metal bar in its place. The bike had bigger problems, though. The wheels, although still present on the playground, were no longer attached to it. As quickly as you read about the wheels, however, is how quickly another boy absconded with the back ones, using them to drive some invisible vehicle down a long and reasonably steep dirt hill toward parts unknown. By then, some of the children had lost interest in the few pieces of the bike that remained. Jimmy, however, held firm to the one remaining and detached front wheel, and Teacher Tom had an idea.

Despite usually letting kids figure out what loose parts represent, Teacher Tom said, "This is a steering wheel. One of you can use it to drive this wagon." He pointed to a trusty (and rather rusty) metal wagon that he, himself, used as a child. One of the older boys quickly accepted the challenge, but as soon as it started moving downhill, his expression turned to worry and he quickly abandoned the ride. He took the "steering wheel" with him to play elsewhere.

Jimmy, who was by far the youngest and smallest in the class, wasn't giving up on Teacher Tom's plan so easily. Confidently, he walked up to the wagon and said, "I try." It took him a bit of effort to climb in, but he made it. And then, like he did on the tire swing I wrote about in a previous article, he said, "Push."

The wagon wasn't moving on its own, despite pointing downward on the dirt hill. Teacher Tom replied in a respectful tone, "I'm not your Mom. Moms help people. I'm your teacher; teachers will teach you."

Lest I take offense to his comment (hey, I help and teach, don’t I?), his words resonated with Jimmy, and Jimmy started to thrust his body forward, engaging the wheels of the wagon. Holding the steering handle but not turning it, he drove straight into the backpacks that were hanging on the outdoor hooks. Not far. Soft landing.

Teacher Tom straightened the path of Jimmy's wagon and provided him with a brief tutorial about steering. Now, here I am, an adult who knows a thing or two about physics, and a thing or two about two-year-olds. My confidence wasn't great that Jimmy wouldn't end up in a pile of wood chips, or perhaps crash into a gaggle of other little humans. He didn't have a license to drive that thing.

But lo and behold, Jimmy steered correctly, and dang if he didn't make it all the way down the hill without using small bodies as speed bumps or taking out the garden along his way. He drove it...well. Yes, he drove it very well.

Then, looking pleased as a pumpkin, he got out easily and moved on.

So, yeah, Teacher Tom is good at sitting. My daughter is right. But she went on to clarify: "He's good at sitting and waiting to see if kids can figure things out. But if they need him, he helps them."

As parents, our job is to "sit" in a way that allows children to have the time to think critically, to solve problems on their own whenever possible, and to help them finish each day trusting themselves a bit more than they did the day before. They accomplish most of this, of course, through their critical work of play. That's the kind of sitting I want to do.